What California Was Like Before It Became American

Sort of Like LA Is Now But Without Air Conditioning

In the wake of the LA riots, many protestors and more than a few pundits seem to agree: America has no claim on California because it rightfully belongs to Mexico. As it happens, the LA of today is a throwback to the final decades of the Mexican era when “a confusion of revolution, counterrevolution, graft, spoliation and social disintegration” ruled the day.

The fact that they know nothing of their history, Mexican or American, does not stop TV talking heads from talking about it. “Remember that California was part of Mexico, all of the Southwest is Mexico,” said former Univision anchor Maria Elena Salinas on CNN while discussing the ICE protests. “The roots are really deep in that region, and what they’re saying is ‘no, not in our community.’”

“Our community?” Who’s the us? Yes. California was once part of Mexico, but Ms. Salinas made a major metadura de pata, or, as we say in English, faux pas. She failed to preface her remarks with a land acknowledgement recognizing the indigenous people the Mexicans more or less eliminated.

Which tribe deserves the apology is anyone’s guess. Before the first Spanish arrived, there were at least 100 different tribes in the state, and they were as undeserving a lot of Indians as the continent produced. In 1775 Spanish explorer Pedro Font was appalled by all the mindless violence.

The Indians he saw were “in constant warfare between the different villages,” as a consequence of which, “they live in continual alarm, and go about like Cain, fugitive and wandering, possessed by fear and dread at every step.” Font and just about every other European visitor were aghast at the “nakedness and misery” in which most of these early Californians lived.

“They are certainly a race of the most miserable beings, possessing the faculty of human reason, I ever saw.”

This wasn’t just some sort of ignorant Eurocentric putdown either. Some of these explorers, like British Captain George Vancouver, had seen Indians on both continents and admired many of them, but not the Californians. “They are certainly a race,” wrote Vancouver, “of the most miserable beings, possessing the faculty of human reason, I ever saw.”

It was not until 1769 that the Spanish chose to colonize Alta California as they called it, literally “high California,” a translation that would ring even more true in the age of the friendly corner cannabis store.

This incursion would prove to be dramatically more benign than the Cortez-led incursion of Mexico more than two centuries prior, and yet its impact was very nearly as powerful. Leading the charge with an incredibly light brigade was Father Junipero Serra, who, like most of the early Franciscan missionaries, had come directly from Spain.

For the record, the Spanish are as “white” as any other Europeans. This DNA-dissection would be unnecessary today were it not for the claim by young Hispanic radicals that America somehow screwed the Aztecs out of California. The Hispanic Californians of the pre-Gold Rush days were ripe for the screwing in any case. Although no one denies that Serra and most of his missionaries were men of extraordinary character, few secular observers applauded the results.

That said, this group of poor and unarmed Spanish missionaries pacified the area from San Diego to San Francisco, converting some 54,000 Indians along the way and building 21 missions. They also named just about every major city in California after a saint or Catholic ritual. Oddly, a state whose courts recently forced the removal of a cross on private property seems somehow okay with having the case adjudicated in “Sacramento.”

In 1821, Mexico broke away from Spain. This ill-starred country shifted to a nominally Republican form of kleptocracy. Although there were only about 3,000 white people in Alta California at the time and likely no more than 100,000 Indians, the sudden shift from a fully Christian state to a boldly secular one caused a major shock to the Indians who depended on the missions and to the Spaniards who depended on the old order. “The old monastic order is destroyed and nothing seems yet to have replaced it, except anarchy,” wrote Monsieur du Petit-Thouars, who visited in 1837.

History repeats itself. If it is too much trouble to remove the names of cities, Catholic icons are fair game. In recent years, as California has descended once more into anarchy, toppling Father Serra statues has become more popular than cow tipping.

Bostonian Richard Henry Dana had just turned 19 in 1834 when he left for his “two years before the mast.” During those years, he would prove to be as honest and accurate an observer as ever visited these golden shores. There was much that Dana liked. The countryside was beautiful and so were the women. The Californians of Spanish descent had good manners, nice voices, and danced well. The frijole was “the best bean in the world.”

“The Californians are an idle, thriftless people, and can make nothing for themselves.”

In those live and let live days before “Hispanics” had mutated into a minority group, Dana felt free to evaluate them as he saw fit. “The Californians,” he would write, “are an idle, thriftless people, and can make nothing for themselves.” That they actually had to buy wine from Boston appalled the young man. Even before California’s beautiful people started squandering their fortunes on Napa vineyards, the country abounded in grapes.

“Among the Spaniards there is no working class,” observed the budding sociologist. The post-mission Indians had grown resigned to “being slaves and doing all the hard work.” Dana bemoaned a “caste” system determined solely by one’s Spanish blood. “In fact,” he wrote in summing up his hosts, “they sometimes appeared to be a people on whom a curse had fallen, and stripped them of everything but their pride, their manners, and their voices.”

In 21st century California, that caste system has reemerged. Ironically, it is the descendants of Indians from Mexico and Central America who are “doing all the hard work.” Today’s elites seem no more troubled by this disparity that the elites of Alta California.

“The final decade of California’s Mexican era was a confusion of revolution, counterrevolution, graft, spoliation and social disintegration as Northern and Southern factions struggled for power in a series of internecine clashes.”

California’s state historian Kevin Starr summed up those years after the rise of the Mexican republic: “The final decade of California’s Mexican era was a confusion of revolution, counterrevolution, graft, spoliation and social disintegration as Northern and Southern factions struggled for power in a series of internecine clashes.” Otherwise, everything was great. Curiously, the Nortenos and Surenos still fight over California, but now as prison gangs.

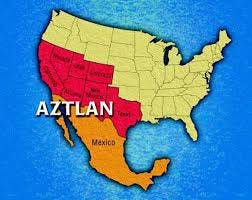

This little history helps put the “reconquista” dreams of today’s radical Latino movement in some perspective. According to one of the movement’s founding documents, El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, only “the brutal ‘gringo’ invasion of our territories” has separated the “northern land of Aztlan” a.k.a. California, from the Mexican motherland. Rightfully, it “belongs to those who plant the seeds, water the fields, and gather the crops and not to the foreign Europeans.”

Is there a nice way in Spanish to say “clueless?” In 1846, one set of largely European descendants, namely Americans, removed another set of largely European descendants, namely the Mexicans, from control of what would soon come to be the state of California.

The Mexican Republic had governed California for only 25 misbegotten years. Hispanics had been there only 75. At the time, there were fewer people of Hispanic descent living in all of California—12,000 max--than there are Eskimos living in California today. By all accounts, these early Californians considered the planting of seeds, the watering of fields, and the gathering of crops beneath their dignity. “California in a nutshell,” said Sir George Simpson in 1841. “Nature doing everything and man doing nothing.”

Richard Henry Dana saw an alternate future for California. He described the Yankees who had married into the culture, as “having more industry, frugality, and enterprise than the natives” and noted that they had already begun to dominate trade and even civic life. “In the hands of an enterprising people,” he enthused, “what a country this might be!”

For a century and a half after America’s annexation of California in 1848, what a country it was. Dana’s prophecy held true. The state was a dynamo of Yankee ingenuity and progress. Gradually, alas, the ruling elites adapted the old Mexican model of governance, and here we are today. For all the chaos and disorder, pool boys still come cheap.

Paid subscribers will receive a weekly installment of my book in progress, Empire of Lies: Big Media’s 30-Year War on Truth, 1994-2024. Sign up today!

Hilarious and educational. ".or, as we say in English, faux pas." A day without a Cashill article is like a day without sunshine.

Big takeaway for me: they lost, and they’re still upset about it.