Stacey Abrams Puts A Green Face on a Grey Old Vote-Buying Scam

Dems Used to Be Discreet When Bribing Votes with Appliances

In watching Georgia Governor imaginaire Stacey Abrams explain the magical thinking behind the preposterous $2 billion grant she received from the EPA, I was reminded of my youthful days working at the Newark (NJ) Housing and Redevelopment Authority (NHRA).

The NHRA gave away appliances, too, and for much the same reason. To their humble credit, the NHRA brass made no bones about why they were giving appliances away, and it had nothing to do with saving the planet.

As most readers know, The Abrams-linked “Power Forward Communities” received a $2 billion grant in 2024 despite reporting just $100 in revenue the year before. As part of the grant agreement Abrams’s NGO had to complete a ‘How to Develop a Budget’ training within 90 days of receiving the grant.

Said Trump’s EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin, "$2 billion in hard earned tax dollars should not have been doled out to this organization for many reasons, especially if they don’t even know how to put together a budget.”

On a subsequent MSNBC program, Abrams explained that in 2023 and 2024, she led a program called Vitalizing De Soto. The program showed residents in small south Georgia town how they could lower costs by replacing energy-inefficient appliances with efficient ones. Of course, having someone else pay for the new appliances saved a whole lot on monthly installment payments.

Abrams thought the program so beneficial that she put together a coalition of organizations to call on Biden’s EPA to roll out the appliance scheme nationwide. It is no coincidence that Abrams’s work in the previous years had focused on turning out Democrats to vote. In reality, the appliance scheme—sort of like “Obama phones”—was just another way to accomplish that same end.

As it happens, I have first hand experience with both voter turnout drives and appliance schemes. They kind of go together. Some years back, I was hired as the special assistant to the executive director at the literally imploding NHRA, an elusive title for a concocted job.

I had two qualifications that endeared me to the Philippine-born woman who ran the show: my family lived in Newark public housing, and I aced her borderline illegal IQ test. An elitist whose role model was the then little-known Imelda Marcos, my “Imelda” took me under her wing.

Ignoring all election laws, Imelda and her figurehead boss—a black “judge” of some sort—illegally threw the whole weight of the Housing Authority behind the incumbent mayor, Democrat Ken Gibson, a political ally of the judge. Imelda admitted that Gibson was “not perfect,” but she thought him to be “best for the city.”

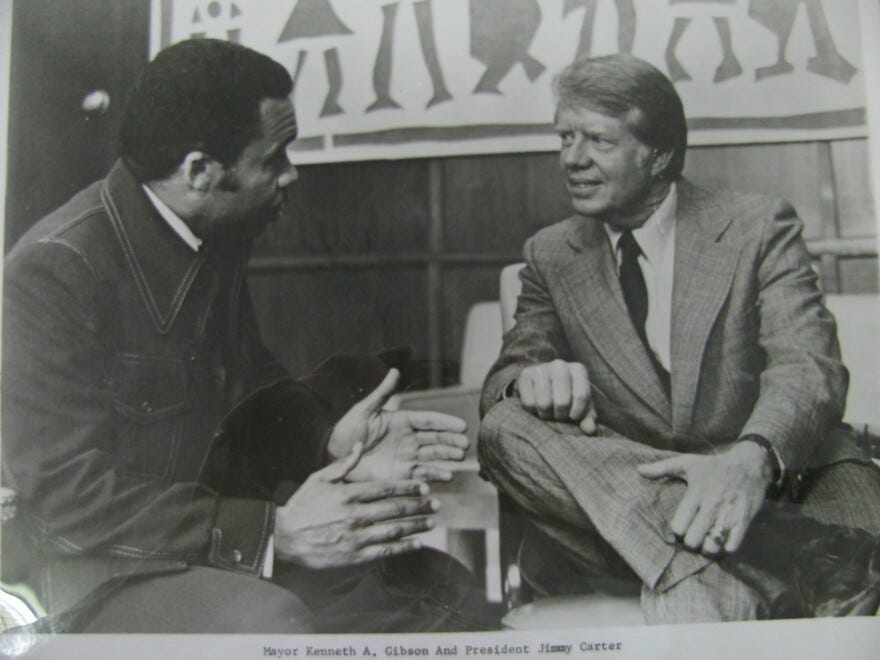

“Not perfect” failed to do Gibson justice. A year before my arrival, a federal prosecutor sought to indict him on tax fraud. According to the New York Times, Gibson had allegedly taken money from his 1974 campaign fund and secreted “more than $75,000 in a Swiss bank account.” The Department of Justice would not allow the charges to be brought. Rumor had it that Jimmy Carter himself quashed the indictment.

Gibson’s chief opponent was City Council president Earl Harris, also black and also a Democrat. On March 31 of that year, about six weeks before the May election, a special Essex County grand jury indicted both Gibson and Harris for arranging a no-show job for an old Italian politico. “Diversity” in action. No one expressed shock or even surprise. This was Newark after all, and these were Democrats.

Imelda ran the agency’s election effort. Sticking around after work each day and on Saturdays to finish my PhD dissertation, I watched as her mostly foreign-born staffers manned the agency’s phones. They were reminding the thirty thousand or so people who lived in the projects why it was in their best interest to reelect the mayor.

What really caught my attention was the way Imelda was rewarding “tenants of influence.” The reward often came in the form of a new refrigerator, the currency of the realm at that time. Refrigerators secured loyalty even better than cash. No one even pretended they were saving energy, let alone the planet.

Sometime that spring I learned that I had been awarded a Fulbright to teach for a year at a French university, starting in September. Now with a graceful exit assured, I could really start having fun with these people.

As the May 11 election approached, Imelda informed the staff, hundreds of us, that we were expected to volunteer a vacation day to help get out the vote on Election Day. Playing along, I was assigned with old-timers, Joe and Sal, to the senior projects in the Italian North Newark where my grandmother lived. Our job was to go door-to-door and escort the little old ladies to the polls, reminding them that if they wanted to keep their apartments, it would pay to vote for Gibson.

We never left the local coffee shop. These guys had great stories to tell about past elections and all day to tell them. The best stories were about the last election in which an Italian candidate and a black one competed for the mayor’s job.

Pointing to the polling site across the street, Joe said, “I voted there six times that day. I was dead people. I was old people. I was all kinds of people. And don’t think they weren’t doing the same thing on the other side of town.” I took him at his word and asked him to pass the cannolis.

After my day near the polls, if not exactly at them, I headed back to the office and spoke to my young black secretary. She was sporting a Gibson pin as big as her head. “Our man gonna win?” I asked.

“Don’t matter who win,” she answered. “Both them n*****s goin’ to jail anyhow.” What she feared most, what everyone feared, was that no candidate would get a majority of the vote. None did, which meant a runoff between Gibson and Harris and another vacation day squandered at the polls.

No longer trusting me to man the polls, Imelda assigned me to deliver fried chicken to the “volunteer” poll workers for the runoff vote. I countered by scheduling a knee operation for that same day. Imelda appreciated the moxie of my gambit.

Despite my absence, Gibson prevailed. A month later Imelda called the senior staff into a conference room in flights of about eight. She told my group, as she told the others, that to retire his campaign debt Mayor Gibson was inviting all of us to a victory breakfast. Knowing what that meant, most of the staffers pulled out their checkbooks. The only thing that surprised them was the amount—$250 or about $750 by current standards.

Imelda went around the room one by one and requested the check. “Is this mandatory?” one fellow asked timidly.

“Only if you’re interested in job security,” she smirked.

When she came to me, I dutifully pulled out my checkbook, smiled, and said, “Should I make the check payable in Swiss francs?” The room froze. Then Imelda laughed, and the whole room laughed with her. Back then, before they started believing themselves wiser than God, Democrats actually had senses of humor.

Stacey Abrams proved how out of touch she is with regular people. She was running for governor in Georgia. It was the week of the Georgia-Tennessee football game. She had a long TV interview dressed in a bright orange outfit. Orange is the color of the Tennessee volunteers. I don't know how much it contributed to her loss, but it wasn't too sharp.

Great story and entertaining. Stacey Abrams makes pond scum look good.